Abstract

Empirical studies in complexity matching have sought to measure coordination of complex signals. Here we review the historic relevance of what is meant as ‘complexity’ and how that was led to a measurement of coordination between coupled agents. Then the extension of complexity matching theory to psychological and cognitive sciences will be reviewed here. The methods used to capture complexity from signals in social interactions will be outlined to understand the strengths and limitations of the methodology. We then conclude with discussing how prior methodology and relevant work on studying structural resonance can help inform the endeavor of finding complexity matching of brain responses and auditory stimuli.

Introduction

Throughout this paper the word ‘complexity’ will be used heavily, touching upon the diverse span of its use in the scientific literature. More often than many researchers like to admit, the use of the word reflects a confusing etymology in which it can be encountered in the wild as an interchangeable word for meaning ‘complicated’ or ‘not simple’. Before you encounter the pervasive use of ‘complex’ or ‘complexity’ in this paper, we will define what it means for cognitive scientists in reference to the general use of ‘complexity’ and connect that to the methodology for measuring such a phenomenon.

Complexity

So, what is complexity? Well, we can start by talking about what it is not. On the other side of the epistemic table exists reductionism. Rene Descartes, being a famous proponent of this way of knowing, emphasized that we can best understand the natural world by understanding the most irreducible, fundamental component of some natural structure. This Lego block like epistemology compartmentalized natural phenomena, in the hopes of finding the smallest foundational block from which all other blocks are made out of. In other words, if someone can find the smallest unit in a system and understand its structure, then we will be able to also understand the larger structure of which it composes. This works under the assumption that interaction between blocks of the system architecture only tell us about their association, disregarding that there is more to know about a system other than the sum of its parts. Not to mention that scientists eventually find more structure underneath the presumed foundational unit of study, much how the atom is now studied as a complex system of its own.

Conversely, the recognition of complexity in systems theory looks at the interaction of system components. Herbert Simon (1981) points out that the focus on component interaction gives rise to the emergence phenomena. Which, unlike reductionism, presents a case for the limitation of only looking at the sum of its parts. Mitchell (2009) references many natural systems as examples of emergence e.g., ant colonies, the immune system, the world wide web, economies, and of course the brain. Ants much like neurons, are simple and low-level components of their systems. On their own they demonstrate a limited behavioral capacity, but their coordinated interactions demonstrate behaviors not expected to arise from observing the individual components (Hofstadter, 1979).

The above-mentioned examples and descriptions of complexity have been under the umbrella of what is termed as ‘organized complexity’. Weaver (1948) explains that a system in which the component interactions are not random and correlated, define organization behind the system complexity. On the other hand, systems with a large number of components and random component interactions are defined as ‘disorganized complexity’. The systems we refer to in this paper, unless otherwise noted, will be of organized complexity. Once we can know whether a system is organized or not, one can also measure the correlated component interactions to get a measure of how it is organized. Simon (1981) first argued that these system organizations can be best described as types of hierarchies when it comes to organized complexity. There can be an explicitly described formal hierarchy, in which a level of a system has direct influence and control over sub-components. We can refer to government hierarchies in which command and rank directly shape the organization of the system. Although such systems exist, it is more common to encounter a system where the formal hierarchy definition is irrelevant. Hierarchy in the non-formal way simply refers to the embedded relationship of system components. Although such a definition may seem vague, it allows room for looking at component interactions that do not follow a top down control and can involve bidirectional influence in the hierarchy.

Hierarchical Temporal Structure

A hierarchical systems organization can arise from the interaction of simple functions. A prime example of this comes from the 2-dimensional Ising model (Ising, 1925; Onsager, 1944; Kim, 2011). The Ising model is a classic example of self-organized criticality, in which the atomic spins and their neighbor interactions showed magnetic phase transitions to occur without explicitly programming them. A critical state from the Ising model shows long-range spatial correlations of atomic spins, meaning that the interactions from a section of the lattice can influence groups of atoms at longer distances. The hierarchy in this system does not come predefined in the same way that one might think of when thinking of a formal hierarchy such as a presidential cabinet. Instead, the dynamics of the atomic spins create correlations from their neighbor interactions that travels across the map and a hierarchy of magnetic interactions across space emerges. Similarly, Hierarchical Temporal Structure (HTS) refers to correlations of system component interactions over the time domain. The term (HTS) was coined in (Falk & Kello, 2017) to measure temporal variations of acoustic energy of infant directed speech and adult directed speech at multiple time scales. These time scales referred to the embedded hierarchical organization of linguistic units such as phonemes, syllables, phrases, and utterances. Moreover, the importance of the embedded organization in language has been comparatively studied in music as well in terms of syntactic organization. A shared relation between language and speech organization has led to studies finding meaningful similarities in neural processing. More specifically, syntactic processing in the brain shares the recognition the embedded relationship of both linguistic and musical units to parse the temporal variation of the signal (Patel, 2003). In Cognitive Science, the focus on time domain measurements comes paired with the dynamical & complex systems approach. Simply put, a dynamical system consists of a state space whose trajectory over time is defined by a dynamical rule. This contrast classic symbolic and connectionist approaches that would focus on the representational content of states and the underlying mechanisms that would generate them. A focus on the state space trajectories also allows for the study of external and internal influences of the system, which in the Cognitive Science literature has been used to combine approaches of embodiment (Beer, 2000).

In this paper we review how the theoretical frames of complexity and dynamical systems have been extended in empirical work to develop methods for measuring the coupling of complex systems. The focus will primarily surround empirical work of speech and music as well as other signals seen in social interaction. We bring in current work pointing at the resonance of HTS from these signals e.g., phonetic levels in speech, seen in brain responses. From such work, we propose what it means to have coupling of complex stimuli and brain responses, along with the importance of structural resonance of these signals and what an empirical method would need to consider to successfully measure it.

Coupled Behaviors

A dynamic systems approach on coupling can be traced back to the field of Synergetics, originated by Hermann Haken. Synergetics looked at how a system’s activity evolved over time as described by either external or internal control parameters. An example of external control parameters can be seen in the power input of a gas laser into an electrical current which modulates the rate of change of phase-locked activity. On the other hand, human hormones and neurotrasmitter activity has been modeled as having internal control parameters arising from their correlated interactions (Haken, 1969; Haken & Graham 1971). The latter example is akin to self-organization and the emergence phenomena, where the meaningful coupling of component behavior gives rise to the control parameters that best describe the dynamics of the system. Principles of Synergetics applied to human behavior were initially popularized by Kelso’s work on the emergence of interlimb coordination. Briefly put, cross-correlation of cyclic limb movement demonstrated evidence for mutual-entrainment. Varying cycling frequencies between limbs were also able to demonstrate non-arbitrary, subharmonic relationships (Kelso, Holt, Rubin, & Kugler, 1981; Haken, Kelso, & Bunz, 1985). Such work allowed for the coordination of human behavior to be understood as an emergent process deriving from non-linear, limit cycle oscillatory dynamics. Later work by Schoner & Kelso (1988) formalize principles of emergence in non-equilibrium systems and their stochastic, non-linear temporal patterns to connect macroscopic behavior coordination to the microscopic. Setting a common language of temporal dynamics and coordination allowed for Cognitive Science to generalize the functionality of cognitive processes across scales of measurement. An example given central to our review is the connection between non-linear temporal dynamics of neural activity to social behavior. This paper provides further perspective on this concept through the proposal of studying the coupling of complex input stimuli signals and brain responses, but we first explain the historical progress of related coupled behaviors in the field.

Following the momentum from the Synergetics work, researchers started to look at the coordination involved in synchronizing motor output with the temporal relationships of the environment. Such a focus of study came to be known as Sensory-Motor-Synchronization (SMS) and combined behavioral experiments like the pervasive finger-tapping paradigm to the more recent neural activity focused designs (Iversen & Balasubramaniam, 2016). Insights from finger-tapping experimental paradigms have shown there to be a non-trivial synchrony, even when participants are told to match their tapping to a set of regular auditory beeps. The foundational work of SMS claims that such a process shows evidence for anticipatory processes. The regulatory activity of the coordinated synchrony therefore being controlled by phase and period correction (Repp, 2005; Repp & Su, 2013). Work in SMS have traditionally been able to demonstrate a strong advantage for auditory stimuli (McAuley & Henry, 2010; Patel, Iversen, Chen, & Repp, 2005). New work has been able to challenge the simple assumption that SMS has modality specific biases by showing how a tuning in stimuli presentation can illicit stronger responses from participants. Meaning that the presentation that works for one modality may not be balanced if directly transferred to another one (Gan, Huang, Zhou, Qian, & Wu, 2015; Hove, Iversen, Zhang, & Repp, 2013; John R Iversen, Patel, Nicodemus, & Emmorey, 2015). Furthermore, beat perception studies have shown anticipation as neural activity synchronization continues in the absence of an expected beat. Prediction models have established a link with the motor planning system as aiding with sensory prediction (Patel & Iversen, 2014). The signals of interest we review in this paper are auditory, aligning with the simple case for coordination in SMS.

The anticipation work provided through the SMS framework was then taken a step further in what is termed as strong anticipation. Anticipation in the ‘weak’ sense, was defined as some system predicting future states to another system in which it needs to coordinate to (Dubois, 2003). For anticipation to be strong, the two systems in coordination are defined as making up a new whole system. This means that the lawful relationships between a system A and system B are coupled strongly enough where prediction of future states is not necessary, thus creating a new system C. Furthermore, because of such a strong coupling of the global dynamics of systems A & B, strong anticipation is measured by the coordination at multiple scales as opposed to a scale unit specific modulation as seen in SMS. Strong anticipation provides a framework for looking at coupling that does not necessitate internal representational models between coordinating systems. Instead, it looks at systems as being embedded in a hierarchical organization. In which both systems A & B can be observed as having their own identifiable properties, but through their interactions at multiple scales of measurement can define a higher-level system functionality (Stepp & Turvey, 2010). One of the first empirical examples for strong anticipation with the human perceptual system was a new take on the finger tapping experiments from SMS. Participants were instructed to synchronize their tapping to a chaotic metronome, which is not linearly predictable. Results showed that the functions of the fluctuations from the metronome and participants’ tapping had similar slopes, which provided evidence for the adherence to long-range correlations in signals (Stephen, Stepp, Dixon, & Turvey, 2008). Evidence for strong anticipation in interpersonal coordination has also been shown when participants coordinate pendulum swings. The series that coupled participants produced demonstrated correlations with their scaling exponent. Local, faster time-scale dependencies also were very limited in explaining the coordination. About ~30% of analyzed windows showed significant cross-correlation. This showed that although there may be some weak anticipation process involved, that it could not describe the behavior as a whole. The process for which strong anticipation is measured in interpersonal coordination was then dubbed as ‘complexity matching’ in this study, and it is the language that later studies use to describe similar scenarios (Marmelat & Delignières, 2012).

The formal description for complexity matching came from the study of complex networks in the physics literature, in which the similarity of complexity between networks determines the extent of information exchange (West, Geneston, & Grigolini, 2008). Empirical adaptations to this concept were continued through the study of interpersonal coordination. Previous work assumed that global variability was solely responsible for complexity matching and that local interactions were primarily responsible for weak anticipation. To test this assumption, researchers use the same pendulum swing interpersonal coordination task but varied the uncoupled frequencies in dyads. This resulted in having more relative phase shifts acting as increased local corrections when the dissociation between dyad’s movement complexity increased (Fine, Likens, Amazeen, & Amazeen, 2015). Multi-fractal analyses have also been proposed to distinguish the matching attributed by local adjustments and the global statistical dynamics assumed by the prototypical complexity matching framework. Although results from multi-fractal methods allow for the distinction of local versus global matching, it does not discount local adjustments as being signs of weak anticipation but instead makes room for a combined approach of the behavior when doing complexity matching (Delignières, Almurad, Roume, & Marmelat, 2016). Furthermore, multi-fractal analyses have been used to present the argument for complexity matching methods being able to capture more ecologically valid data (Almurad, Roume, & Delignières, 2017). As we have referenced in this paper, the standard empirical framework for complexity matching has been in interpersonal coordination tasks. Moving away from movement data, a study tested for complexity matching between affiliative and argumentative dyadic conversations. They correlated their scaling functions from their produced signals, which in this case were speech. Results showed that there was more complexity matching between speech signals in affiliative conversations in comparison to argumentative (Abney, Paxton, Dale, & Kello, 2014). An extension of this approach sought to test whether complexity matching could happen in bilingual conversations. The experiment had bilingual participants (English & Spanish) engage in affiliative conversations under three conditions. The conditions had participants talk both in English, both in Spanish, or one in Spanish and the other in English. Results showed that complexity matching was seen with no significant difference across conditions, meaning that participants were able to converge their speak across languages and while speaking different languages. Further analyses also showed that there was also a matching of the lemmas of lexical words (lexical matching) across languages. The longer timescales of the scaling function from produced speech were shown to be the most relevant in complexity matching. With these results the authors found it clear to relate the matching observed to be related to a convergence of prosody i.e., the similarity in how informational linguistic units are organized. Which can explain how speech convergence can be understood as generalized coordination behavior robust to linguistic differences across languages (Schneider, Ramirez-Aristizabal, Gavilan, & Kello, 2019). Moving beyond typical interpersonal coordination, a complexity matching study looked at bimanual coordination as a case for intrapersonal coordination. They put into question the interpersonal coordination framework for complexity matching and provided another example of coordination between complex systems that was not between people or the simple metronome synchronization case. Stronger complexity matching was seen in the bimanual task where participants had to syncopate their finger tapping between hands versus when they had to match between participants (Coey, Washburn, Hassebrock, & Richardson, 2016). Complexity matching has also been shown to not be limited to the virtual realm. A study had participants located in different rooms and tasked to find each other and get to know what each other through interacting virtual avatars. They used avatar positions and velocity of movement to have long-range correlated time-series of their interactions. The movement between dyads’ avatars had a significantly stronger degree of complexity matching when comparing the time-series of random participant pairings who were not dyad pairs in the experiment (Zapata-Fonseca, Dotov, Fossion, & Froese, 2016). The analysis used to get a HTS function for the movement dynamics was the same as used by Abney et al., (2014). Several analyses have been used to measure complexity of a signal to then test for their matching as previously referred to in this section. In the next section we break down the varying methods to understand the strengths and weaknesses of methodology used to point towards the complexity matching effect.

Methodology

The understanding of a signal’s complexity has been the precursor for relating the HTS of coupled behavior i.e., complexity matching. The goal of these measurements is to understand how the activity of the signal varies at multiple timescales and see how the scaling takes shape. Although the complexity matching literature has used several methods to capture the statistical complexity of a signal, there are also other complexity measures that have not been adapted in complexity matching studies. Here we start by outlining methods for capturing HTS in the complexity matching literature to understand the limitations of their implementations. Then we conclude by explaining how complexity of a signal can be related to another. We hold speculation for new methodology in the following section as we propose protocol ideas for future studies trying to do complexity matching with neural oscillations.

Detrended Fluctuation Analysis

In relevance to the Cognitive Science literature, the detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) was first used by Stephen et al., (2008) to propose a method for capturing long-range correlations of a time series. The purpose of using this method was to make a case for strong anticipation, which involved the activity of a signal at multiple time scales. This is in comparison to looking at correlations that happen at specific frequency rates. The use of DFA was first established in a DNA sequencing paper which tried to consolidate a method for understanding the meaningfulness of long-range correlations in nucleotide sequences (Peng et al., 1994). Such a method was an extension of the classic fluctuation analysis, in which the purpose of DFA was to handle non-stationary activity through a detrending process. Successful mitigation of non-stationary trends in a time series is meant to demonstrate the scale invariant relationship of the signal.

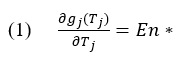

The process can be broken down into two steps. First a given time series (x_i) is shifted by its mean (see Equation 1). Then, the integrated series (X_t) is segmented by windows of different time scales (n) in which the integrated values are fit linearly per window (Y_t) and the mean squared residuals F(n) are calculated as the fluctuations of the signal (see Equation 2).

The fluctuations F(n) are a measure of variability at specific resolutions (n), that come from the averaged dispersion of residuals extracted from the local linear fits of the integrated values (X_t). Power law scaling is demonstrated through log-log plotting of F(n) over (n) in a fluctuation plot and its trend linear as delineated by the α scaling exponent which approximates the Hurst exponent. This is in reference to the original work demonstrating a heuristic measure of long-range dependence in signals dominated by stochastic properties, termed the Hurst exponent (Hurst, 1951). Newer measures such as DFA are applied to varying natural data in the attempt to estimate Hurst scaling.

The DFA method faced criticism for its ability to create artifactual curvature in the fluctuation plot. Despite its original intent to handle non-stationary noise, the robustness of the method was shown to be limited to signals with either purely stationary or weak-nonlinear trends (Bryce & Sprague, 2012). Results from the testing of artifactual curvature in DFA put many studies into question. In the case of complexity matching or the related strong anticipation studies, the strength of correlations between α scaling exponents can be problematic for unknown variability coming from artifactual curvature. Newer methods have attempted to go beyond and use a multi-fractal version of the DFA, which is further reviewed in this paper.

Allan Factor

The first use of Allan Factor for complexity matching was implemented in a dyadic task, comparing affiliative and argumentative conversations (Abney et al., 2014). Motivations to use the Allan Factor method were to bypass issues from DFA and to practically analyze rich natural data and not use the whole raw signal. As previously discussed, the DFA was shown to add artifactual curvature, which would be problematic for signals who have meaningful deviations of perfect self-similarity. A later study which looked at the HTS of various natural sounds using Allan Factor e.g., bird songs, whale song, classical music, jazz, conversations, monologues, and so on, found that certain sounds had distinct HTS. Despite jazz and conversations having obvious perceptual differences when we listen to them, Allan Factor analysis demonstrated that such two categories of sound could be grouped together as following a distinct scaling when comparing it to classical music, which was found to have similar scaling as thunderstorms along with other comparisons that broke from the norm of signals with scale-invariance (Kello, Bella, Médé, & Balasubramaniam, 2017). Many of these signals have characteristic flattening of variance and it differs across HTS groupings, therefore a method that can capture meaningful curvature in rich natural data is useful for the comparison across signal types.

For the Allan Factor to be able to normalize across scaling characteristics of signals, the method relies on an event series for its analysis of dispersion. The event series in the Abney et al., (2014) study were based on acoustic events. This is in reference to Pickering & Garrod’s (2004) interactive alignment model, in which it describes different levels of linguistic units being affected through social interaction e.g., semantic, syntactic, phonological, and phonetic, and the acoustic onsets being markers for relevant and perceivable events of acoustic energy (Cummings & Port, 1998). Future implementations of Allan Factor use peak-amplitude events due to its universality in signal processing and simplicity in identification, although events can be extracted in other ways. We stick to further explaining Allan Factor through peak-amplitude events here.

The method starts by taking a signal, often down sampled, and segmenting it into 4 min segments. For each segment the Hilbert envelope is calculated and from the produced amplitude envelope peaks are chosen in two steps. First maximal peaks are identified through a 5 ms sliding window. Then, any peaks below the H amplitude threshold are zeroed out to clean up irrelevant noise peaks occurring in low amplitude moments of the signal i.e., during a pause in speech background noise can be picked up. The H amplitude threshold is set so that one event is identified every 200 samples. Then the Allan Factor is used to take the variance at different timescales of events. At timescale T, the average of squared event differences across windows is divided by twice the mean of events across windows (see Equation 3).

This essentially gives a coefficient of variance at timescale T for what is typically done at 11 levels of resolution spanning from T ~ 30 ms to T ~ 30 s. Then results are projected in a log-log plot. The scaling of A(T) presents a power law relationship in the signal when α>0 in T^α and a flattening of such a scaling is akin to short-range correlations.

Multi Fractal

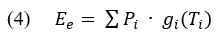

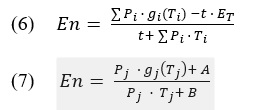

A study by Delignières et al., (2016) revisited data on bimanual and interpersonal coordination along with synchrony to a fractal metronome using multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MF-DFA). Motivations for the multifractal implementation were to provide a clearer picture on local adjustments versus global attunement to better define complexity matching. We have reviewed the skepticism cast on DFA due to artifactual curvature but MF-DFA use in complexity matching has not explicitly been described as a response to that. The MF-DFA starts in the same fashion as DFA (see Equations 1 & 2). Once you have the detrended fluctuations F^2 (n,s) for window segments n of size s, the next step is to average them to the qth order (see Equation 4).

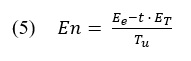

In order to get the generalized Hurst exponent h(q), a range of q values are considered and then averaged together. The q exponent cannot take a zero value, but Delignières et al., (2016) provides a logarithmic procedure (see Equation 5) as an alternative when they test q at an integer range of -15 to +15.

Also, several window sizes are used to test local adjustments versus global attunement, although one can stick to a one window size if that is not the case.

Motivation to use MF-DFA has been to provide a clearer picture of the complexity of a time series as opposed to ‘monofractal’ methods. The metaphorical description of a ‘clearer picture’ points to monofractal methods as being limited due to only being able to capture the outline of a portrait. On the other hand, multifractality can outline subsystem details that would give more fidelity to the assumption that the picture in question is indeed of a person and not a stack of fruits. A recent paper pushed this argument, saying that assumptions of nonlinearity and within system interactions may have faith misplaced with just monofractal methods. The presented argument also did not make clear what cognitive analog multifractal cascades are responsible for capturing although it firmly called for the necessity to include multifractality (Kelty-Stephen & Wallot, 2017). Such a provocative claim explicitly explained that it could not discount monofractal methods as describing how information is embedded across scales, in the fashion to which Allan Factor has been used to measure HTS. Nevertheless, the original presentation of MF-DFA was purposed in proving its practicality for higher performance on shorter time series, which in our review we stick to as the solid consideration for such a method.

Relating Signals

Apart from getting a measure of complexity, the process of complexity matching then needs to find a way to relate those measured complexities. An example of relating signal complexity has been used in the complexity matching literature. The cross-correlation method has been initially useful in demonstrating phase and period correction in SMS studies as a marker for synchronization (Repp, 2005; Repp & Su, 2013). Given the comparison of two signal functions f and g, the method takes their dot product (g⋆f) and correlates them at different lag points (e.g., -1, 0, and 1). The comparison between lag points allows to check how much one signal needs to be shifted in order align with another. Furthermore, one can pick a sliding window size to adjust for the resolution of cross-correlation, a window with fewer data points will compare smaller activity. The Marmelat & Delignières (2012) study adjusted windows in their cross-correlation to test local dependencies in an interpersonal coordination task. In their analysis, lag 0 correlations were meant to find simultanous event alignment and in comparison lag ±1 tested for short-range dependence between participants.

Results comparing scaling exponents and cross-correlation demonstrated a difference between the coordination of local adjustments and the matching of global activity. Researchers used such results for proof of differentiating between anticipaiton of local activity (weak anticipation) versus the anticipation that seeks to match the activity at a global scale (strong anticipation). Because cross-correlation could not fully explain the matching of scaling exponents in measured signals, the literature moved to using the term complexity matching. This is due to the theoretical predictions made by West & Grigolini (2008), in which the global activity of a signal is restricted by the complexity of the system generating it. In sum, cross-correlation was solidified to be useful in revealing local adjustments, but the complexity matching paradigmn calls for the comparison of the global scaling of a signal. Other methods have been used to provide evidence for coordination and synergies of behaviors. This includes cross-spectrum analysis which is essentially cross-correlation of the frequency domain. As well as cross recurrence analysis which measures the stability of similar activity across various embedding dimensions. Coordination literature have used such methods to provide evidence for the coupling of interpersonal and intrapersonal coordination of motor movements (Zbilut & Webber, 1992; Marwan, Wessel, Meyerfeldt, Schirdewan, & Kurths, 2002; Riley, Richardson, Schockley, & Ramenzoni, 2011). On the other hand, complexity matching uses a measure of HTS and correlates the two HTS functions. Such a correlation relates scaling instead of independent state spaces over time. The measurement of HTS retrieves a unified complexity measure across scales as opposed to sampling varying embedding dimensions. This allows one to look at the behavior as a whole and to make inferences for which timescales may be more relevant in the coupling given that scaling demonstrate how scales are related to one another in their dynamics.

Structural Resonance

So far, we have reviewed the historically relevant complexity matching studies and the methodologies involved. Empirical work has focused on interpersonal, intrapersonal, and adjustments to a chaotic metronome. From these we have seen that the work touches upon two modalities of information, movement and speech production. The procedure for finding complexity matching thus involves measuring the scaling over several timescales and correlating it to the corresponding signal from the coordinated behavior at hand. From a theoretical point of view, the production of the signals come from complex systems whose structure shape the signal. Originally modeled through complex networks (West & Grigolini, 2008), the complex structure of the networks determines how receptive they are to signals. Namely, being the most sensitive to signals with the same complex structure as the receiving network. Therefore, information is maximally transferable when communicating networks have matching complexity. Advancement in theoretical work has been interested in tackling how the brain could do complexity matching, as measured by the global cortical dynamics (Allegrini et al., 2009; Mafahim, Lambert, Zare, & Grigolini, 2015). Using data from electroencephalograph (EEG) measurements of resting states in participants, it was seen that spontaneous brain activity generated ideal 1/f signals. Ideal in this case characterized by the scaling exponent μ≈2 of renewal events. In which such events are independent and reoccurring, while still being able to characterize extended memory in a system. In connection to predictions by complexity matching theory, it is posed that the brain is most sensitive to not just 1/f, but specifically to its μ≈2 scaling. In criticality theory, μ<2 is descriptive of systems without stable extended memory while μ>2 describes an extended memory in which its stable state would take an infinite amount of time to converge from an out of equilibrium state. Many natural systems produce 1/f activity, although they may deviate from the concept of ideal event scaling. Such a pervasiveness of 1/f has led to the hypothesis of metastability. Meaning that correlated activity across multiple scales follow a homeostatic process in which ideal activity is an attractor state in the face of perturbations to the system. Furthermore, it allows for flexibility in adaptation to state changes (Kello, Anderson, Holden, & Van Orden, 2008; Kello et al., 2010). The brain then being malleable enough to attune to varying signals while also strong enough to come back to its original shape.

Empirical work demonstrating complexity matching of external stimuli and the neural oscillations has not been seen so far, or at least not directly investigated (*see addendum). There may be many reasons for why that is, including the sociology of science, lack of collaborations, debates of theoretical predictions and so on. We have reviewed how the DFA has faced criticism even when working with data less noisy than brain responses, and the argument brought forth to implement multi-fractal methods to capture clearer insights. Furthermore, EEG methods which have been typically used to capture cortical dynamics face many limitations in their experimental set up to avoid artifact production, something which behavioral experiments in the complexity matching literature do not need to worry about as much. From an empirical point of view, the biggest challenge is to control for as much cortical noise as possible if we would like to test how the structure of a stimulus can be related to a brain response. In reference to the metastability theory and complexity matching predictions, we should not expect that the brain is too easily perturbed that it will have the same extent of complexity matching that has been seen in behavioral experiments. On the other hand, it does lead us to believe that the flexibility of attunement in cortical dynamics should be sensitive enough to reflect the perceived structure of an attended stimulus. The challenge is that this becomes a needle in the haystack situation. The needle being the stimulus structure resonating in the large haystack of cortical dynamics pervasively ringing a 1/f tune.

Much of the advancement towards complexity matching theory, both theoretical and empirical, has been a relatively recent endeavor. Despite this, the idea of relating environmental complexity to brain dynamics is not as new. A relatively older study set out to explicitly match complexity from environmental stimuli to cortical dynamics (Tononi, Sporns, & Edelman, 1996). They used a cortical vision neural network model instead of directly measuring brain responses and their stimuli were a set of elongated vertical or horizontal bars. They compared the visual model to a randomly connected version of the model and measured the entropy of the stimulus and model activity. The matching was done by taking a difference between stimulus and model entropy, and results showed that the random connectivity in the model had a significantly bigger difference than the relevant functional connectivity. Empirical work has made advancements in methodology to relate complex natural stimuli and brain response. A study by Lalor & Foxe (2010) developed what is termed as Auditory Evoked Spread Spectrum Analysis to have a brain response using EEG with high temporal resolution. As it relates to our purposes of complexity matching, the limitations to this technique is that it requires an averaging over multiple presentation blocks, ~48 mins in their study. It also is stimulus driven by requiring the use of the stimulus amplitude to do least squares estimation on the response, as well as responses being akin to Event Related Potentials which do not directly reflect the complex structure of the signals. In another case, Skoe & Kraus (2010) describe a method for finding neural synchrony to auditory stimuli using complex Auditory Brainstem Responses (cABR). Stimuli take a short clip of any complex auditory stimuli, typically no more than 10 seconds long, and present it ~2000-3000 times. The collected cABRs have high temporal and spectral resolution which holds enough information to reconstruct the signal and play it back, sounding very similar to the original stimulus. Furthermore, the use of natural speech stimuli presented at isochronous intervals have been used to demonstrate hierarchical cortical tracking of semantic units (Ding, Melloni, Zhang, Tian, & Poeppel, 2015). Neural responses show tracking occurring at the sentence level (1Hz), phrase level (2Hz), and syllable level presented as monosyllabic morphemes (4Hz). Similarly, evidence for a hierarchical system in auditory processing is posited by demonstrating tracking at lower frequencies of phonemic units in natural speech ~155s (Di Liberto, O’Sullivan, & Lalor, 2015). Longer stimuli are also used in the attempt to analyze hierarchical processing of music and speech with lengths closer to their natural lengths ~4:15 mins (Farbood, Heeger, Marcus, Hasson, & Lerner, 2015). They present conditions with scrambled structure at three different timescales of the music separately to trained musicians. Using fMRI, larger musical timescales were found to be processed longer when approaching higher order brain topography in the auditory cortex.

As presented above, there has been much work trying to develop methods and testable hypothesis to understand how complexity of stimuli such as speech and music can be explained to resonate in cortical dynamics. The idea of complexity matching of complex natural stimuli such as music and speech with brain responses is just one of the testable hypotheses in this space of work. The development of a method that can show substantial evidence for complexity matching will have a large impact even outside the complexity matching theory. The problem of the needle in the haystack is what stands in the way. In order to approach this problem, there seems to be two routes to take. One is to put effort into enhancing the hidden signal per stochastic resonance approaches or to use a stimulus driven approach in the extraction of the signal to enhance impoverished features. This type of approach may be informative and present unique testable hypotheses for how to think of complexity matching in brain responses, but it also may be perceived as a less faithful approach to the question at hand. Second is to control for cortical noise as much as possible, in other words, to make the hay as small as possible. This direction is preferable in order to more faithfully compare the strength of structural resonance in cortical dynamics. Careful artifact filtering and pre-processing should be paid attention to because it may not be as obvious as to what in the signal can be considered as noise. We predict that non-stationarities in cortical dynamics may be harder to deal with and thus affect the visibility of structural resonance. A recently more popular method in analyzing complexity in EEG time series is multiscale entropy (MSE). A study reviewed guidelines for the interpretation of MSE on EEG (Courtiol et al., 2016). Such a method of analysis allows for capturing both linear and nonlinear autocorrelations but with the resolution of complexity focusing in the shorter timescales. There has not been a study addressing an explicit finding on a nonlinear autocorrelation for complexity matching, although the literature always assumes that the signals are generated through a nonlinear function. Although scaling functions correlated to check for complexity matching may present nonlinear scaling, the studies have found it sufficient to correlate linear fits. We consider the exploration of MSE to be worth taking in complexity matching endeavors to brain responses, even if all it is doing is giving us a more detailed picture of the aggregate trends. Furthermore, we expect that it would be beneficial to work with an event series as opposed to raw signals of complex auditory stimuli and EEG. Both due to the practical computation, and abstraction of meaningful variation used to bypass expected non-stationaries. The AF method has proven itself to be reliable in several studies involving complex natural stimuli, although there seems to a stronger representation of the longer timescales. This could be mitigated when combined with MSE who is sensitive to activity in smaller timescales.

Discussion

Complexity matching has been used in empirical studies to quantify coordination. In the abstract, the complexity matching theory describes that maximal information transfer between complex networks occurs when they have their structures scale the same way. From an empirical point of view, participants are put into scenarios in which they produce signals in correspondence to a coupled behavior with another participant. Those signals then have their scaling over multiple timescales measured and the scaling exponent of both signals are correlated. The HTS of a signal is said to be non-trivially matched in a dyadic task. Both participants make an effort in how they produce those signals to have a matching. This happens through a combination of local adjustments and global attunement. In the example of coordinating language, we can refer back to the interactive alignment model (Pickering & Garrod, 2004). The model can be summarized as demonstrating two things: the importance of the embedded relationship of linguistic units, and that alignment can happen at various levels of linguistic units. An extreme example of coupling can be through finding synchrony. If two interlocutors can produce continuous speech at the same time with the same information contained, then it becomes a clear indication of coupling. Such an example is exemplary of a parlor trick, but it denotes a perceivably distinct case in which an observer can tell that two individuals are coupled. On the other hand, coordination may be harder to observe in a conversation because it is not obvious how my speech production is aiding the other’s. With the assumption that both speakers want to listen and process as much of each other’s speech signals as possible, speakers will attempt to converge on the same signal ‘frequency’ much like communication between two walkie-talkies. Whether most people can directly influence fast timescales akin to sub-syllabic units is an untested hypothesis. On the other hand, complexity matching in language has shown that the main coupling relation is housed at the longer timescales (Schneider et al., 2019). Studies using Allan Factor analysis to get a scaling function of speech have attributed their measurements as quantifying prosody (Falk & Kello, 2017). It has also been shown that manipulating speaking rate has an effect on HTS of speech (Ramirez-Aristizabal et al., 2018). Which raises another testable hypothesis for whether the longer timescales can be said to facilitate the embedding of smaller linguistic units and thus shaping the alignment of interlocutors.

A recent study has taken complexity matching methods to inform physical therapy for locomotion. They had young and elderly participants, in which the young participants produced a healthy 1/f scaling of their stride durations and the older participants produced signals more akin to white noise, reflecting a drop in complexity (Almurad, Roume, Blain, & Delignières, 2018). The elderly participants showed a two-week sustained correction of their locomotion after walking hand in hand with a young participant for three weeks. Such a therapeutic endeavor to implement complexity matching allowed for interesting testable hypotheses to arise. One of them putting forth the question whether it makes sense to think of a pervasive 1/f signal generator as an attractor to signals that deviate from that. More generally, it also prompts the hypothesis that a signal with ‘more’ complexity can pull a ‘less’ complex signal. Such findings are informative for therapeutic engineering applications beyond locomotion such as virtual agent/chat bot counseling in the mental healthcare space. The movement of counseling and therapy to happen in an online space is meant to increase accessibility for patients who otherwise would find it difficult to physically reach out to their health care providers or live in areas with poor healthcare infrastructure (D’Alfonso et al., 2017; Tielman, Neerincx, Bidarra, Kybartas, & Brinkman, 2017). Complexity matching methods can be applied to understanding the prosody of depression. A study tackling such an issue analyzed counseling sessions of depressed patients and their therapists. One of their analyses focused on the speech produced and found that when comparing the prosody of the counselor to the patient, less depressed patients had similar prosodic features to their therapists (Yang, Fairbairn, & Cohn, 2013). Prosodic features included the fundamental frequency of a speaker and the lag time between the utterance of one speaker to the other (switching pause). The results showed that the therapists had a significantly higher variability in their fundamental frequency compared to the depressed patients and that switching pause was shorter for less depressed patients. These results converge with the idea that turn taking and variability of linguistic units being what underlies complexity matching in speech (Abney et al., 2014; Schneider et al., 2019). Furthermore, prosodic embellishment has been shown to produce HTS that is more complex (Falk & Kello, 2017) and less natural speech has less complexity (Ramirez-Aristizabal et al., 2018).

These hypotheses of regulating complexity through the coupling of a stronger, pervasive 1/f signal can be informative when thinking about complexity matching with brain responses. We know that the brain produces global 1/f cortical dynamics, and that theory predicts that sensibility is strongest for signals akin to it. We also know that the brain is flexible and that the productions of 1/f can be a sign of metastability. This would allow for the combination of sturdiness to a 1/f stable state and sensitivity to attune to varying signals. These theoretical predictions do not say much in terms of how to test for complexity matching with neural oscillations. What it does help in is thinking about complexity matching in the brain as a search for a change in affect from its steady state, or how the structural resonance of stimuli can be captured. This is very similar to the case of doing complexity matching between a person and a chaotic metronome. An example of such an implementation would be to measure the awake resting state of a participant and compare it to the entrainment of a complex signal to see whether the stable state of spontaneous 1/f production can be affected. This implementation requires multiple averaged presentations of a complex stimuli and the length of the presentations would need to be representative of the HTS of the signal, which in the case of natural stimuli such as speech and music would require it to be in the order of minutes. This complicates the length of an entrainment session and makes it harder to keep a participant focused on the task, which will increase the chance of cortical noise. In the case of trying to test whether healthy state neural oscillations can attract weaker, whitened cortical dynamics, one could measure the EEG responses of coupled individuals in a task. This would need the capability to bypass muscle artifacts to which social interactions often require. To remedy this, a virtual reality study could be adapted so that virtual interactions help control for the need of physical exertion (Zapata-Fonseca et al., 2016). We conclude by making the point that complexity matching in the brain requires careful consideration for artifacts in the data because the slightest perturbation is reflected in our cortical dynamics. Despite that, we believe that we can find the corresponding reflection pool to our auditory world.

Addendum

A study tackling many of the issues brought up in this review has been published after the review was written. The study focused on how the correlated structure of music stimuli and the corresponding EEG response can be an index for mediating music listening pleasure (Borges et al., 2019). In brief the experiment had 12 classical music presentations (~2 min length) while participants closed their eyes and they were rated on their listening pleasure after. Although the study did not explicitly make their narrative about complexity matching, we believe that their data do put forth the first example of complexity matching with EEG responses in the literature so far. They did use DFA and correlated slopes of only classical music which as previously mentioned in this paper follows a 1/f scaling structure. This review has shown that there may be some issues with only using DFA and that there is strong theoretical grounding on structural resonance especially at the scaling that approximates the ideal 1/f statistics. However, current endeavors in our personal research at the Cognitive Mechanics lab and our affiliated collaborators have taken this study with great confidence to then propose a study focused solely on establishing complexity matching theory with EEG responses using their methodology for data cleaning and experimental set up. The hope is that their success in using PREP pipeline and Empirical Mode Decomposition to clean and separate the signal without worrying about artifacts can be transferred into an experimental paradigm that tests a variety of complex acoustic signals to see that limits of matching. Putting forth a scientific study that stakes the theoretical claim of complexity matching brings about more theoretical baggage about the information transfer between systems and can open up avenues for testing the theoretical predictions that we have mentioned above.

References

Abney, D. H., Paxton, A., Dale, R., & Kello, C. T. (2014). Complexity matching in dyadic conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Abney, Drew H.: Cognitive and Information Sciences, University of California, Merced, School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts, 5200 North Lake Road, Merced, CA, US, 95343, drewabney@gmail.com: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000021

Allegrini, P., Menicucci, D., Bedini, R., Fronzoni, L., Gemignani, A., Grigolini, P., … Paradisi, P. (2009). Spontaneous brain activity as a source of ideal 1/f noise. Physical Review E – Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, 80(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.80.061914

Almurad, Z. M. H., Roume, C., Blain, H., & Delignières, D. (2018). Complexity Matching: Restoring the Complexity of Locomotion in Older People Through Arm-in-Arm Walking . Frontiers in Physiology . Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2018.01766

Almurad, Z. M. H., Roume, C., & Delignières, D. (2017). Complexity matching in side-by-side walking. Human Movement Science, 54, 125–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2017.04.008

Baronchelli, A., Ferrer-i-Cancho, R., Pastor-Satorras, R., Chater, N., & Christiansen, M. H. (2013). Networks in Cognitive Science, 17(7), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.04.010

Borges, A. F. T., Irrmischer, M., Brockmeier, T., Smit, D. J., Mansvelder, H. D., & Linkenkaer-Hansen, K. (2019). Scaling behaviour in music and cortical dynamics interplay to mediate music listening pleasure. Scientific reports, 9(1), 1-15.

Bryce, R. M., & Sprague, K. B. (2012). Revisiting detrended fluctuation analysis. Scientific Reports, 2, 315. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00315

Coey, C. A., Washburn, A., Hassebrock, J., & Richardson, M. J. (2016). Complexity matching effects in bimanual and interpersonal syncopated finger tapping. Neuroscience Letters, 616, 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.01.066

Courtiol, J., Perdikis, D., Petkoski, S., Müller, V., Huys, R., Sleimen-Malkoun, R., & Jirsa, V. K. (2016). The multiscale entropy: Guidelines for use and interpretation in brain signal analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 273, 175–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.09.004

Cummings, F., & Port, R. (1998). Rhythmic constraints on stress timing in English. Journal of

Phonetics, 26, 145-171.

D’Alfonso, S., Santesteban-Echarri, O., Rice, S., Wadley, G., Lederman, R., Miles, C., … Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2017). Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Online Social Therapy for Youth Mental Health . Frontiers in Psychology . Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00796

Dale, R., Fusaroli, R., Duran, N. D., & Richardson, D. C. (2013). Chapter Two – The Self-Organization of Human Interaction. In B. H. B. T.-P. of L. and M. Ross (Ed.) (Vol. 59, pp. 43–95). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407187-2.00002-2

Delignières, D., Almurad, Z. M. H., Roume, C., & Marmelat, V. (2016). Multifractal signatures of complexity matching. Experimental Brain Research, 234(10), 2773–2785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-016-4679-4

Dubois, D. M. (2003). Mathematical Foundations of Discrete and Functional Systems with Strong and Weak Anticipations BT – Anticipatory Behavior in Adaptive Learning Systems: Foundations, Theories, and Systems. In M. V Butz, O. Sigaud, & P. Gérard (Eds.) (pp. 110–132). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-45002-3_7

Falk, S., & Kello, C. T. (2017). Hierarchical organization in the temporal structure of infant-direct speech and song. Cognition, 163, 80–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.02.017

Fine, J. M., Likens, A. D., Amazeen, E. L., & Amazeen, P. G. (2015). Emergent complexity matching in interpersonal coordination: Local dynamics and global variability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. Fine, Justin M.: Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Box 871104, Tempe, AZ, US, 85287, justin.fine@asu.edu: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000046

Freeman, W. J. (2005). A field-theoretic approach to understanding scale-free neocortical dynamics. Biological Cybernetics, 92(6), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00422-005-0563-1

Gan, L., Huang, Y., Zhou, L., Qian, C., & Wu, X. (2015). Synchronization to a bouncing ball with a realistic motion trajectory. Scientific Reports, 5, 11974. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11974

Grigolini, P., Aquino, G., Bologna, M., Luković, M., & West, B. J. (2009). A theory of 1/f noise in human cognition. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 388(19), 4192–4204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2009.06.024

Hofstadter, D. R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid (Vol. 20). New York:

Basic books.

Hove, M. J., Iversen, J. R., Zhang, A., & Repp, B. H. (2013). Synchronization with competing visual and auditory rhythms: bouncing ball meets metronome. Psychological Research, 77(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-012-0441-0

Iversen, John R, Patel, A. D., Nicodemus, B., & Emmorey, K. (2015). Synchronization to auditory and visual rhythms in hearing and deaf individuals. Cognition, 134, 232–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.10.018

Iversen, John Rehner, & Balasubramaniam, R. (2016). Synchronization and temporal processing. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 8, 175–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.02.027

Kello, C. T., Anderson, G. G., Holden, J. G., & Van Orden, G. C. (2008). The Pervasiveness of 1/f Scaling in Speech Reflects the Metastable Basis of Cognition. Cognitive Science, 32(7), 1217–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/03640210801944898

Kello, C. T., Brown, G. D. A., Ferrer-i-Cancho, R., Holden, J. G., Linkenkaer-Hansen, K., Rhodes, T., & Van Orden, G. C. (2010). Scaling laws in cognitive sciences. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(5), 223–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.02.005

Kelty-Stephen, D. G., & Wallot, S. (2017). Multifractality Versus (Mono-) Fractality as Evidence of Nonlinear Interactions Across Timescales: Disentangling the Belief in Nonlinearity From the Diagnosis of Nonlinearity in Empirical Data. Ecological Psychology, 29(4), 259–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10407413.2017.1368355

Lalor, E. C., & Foxe, J. J. (2010). Neural responses to uninterrupted natural speech can be extracted with precise temporal resolution. European Journal of Neuroscience, 31(1), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07055.x

Mafahim, J. U., Lambert, D., Zare, M., & Grigolini, P. (2015). Complexity matching in neural networks. New Journal of Physics, 17(1), 15003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/1/015003

Marmelat, V., & Delignières, D. (2012). Strong anticipation: complexity matching in interpersonal coordination. Experimental Brain Research, 222(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-012-3202-9

Marwan, N., Wessel, N., Meyerfeldt, U., Schirdewan, A., & Kurths, J. (2002). Recurrence-plot-based measures of complexity and their application to heart-rate-variability data. Physical review E, 66(2), 026702.

McAuley, J. D., & Henry, M. J. (2010). Modality effects in rhythm processing: Auditory encoding of visual rhythms is neither obligatory nor automatic. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72(5), 1377–1389. https://doi.org/10.3758/APP.72.5.1377

Patel, A. D. (2003). Language, music, syntax and the brain. Nature neuroscience, 6(7), 674.

Patel, A. D., & Iversen, J. R. (2014). The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: the Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) hypothesis . Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience . Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00057

Patel, A. D., Iversen, J. R., Chen, Y., & Repp, B. H. (2005). The influence of metricality and modality on synchronization with a beat. Experimental Brain Research, 163(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-004-2159-8

Peng, C.-K., Buldyrev, S. V, Havlin, S., Simons, M., Stanley, H. E., & Goldberger, A. L. (1994). Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Physical Review E, 49(2), 1685–1689. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.49.1685

Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X04000056

Riley, M. A., Richardson, M., Shockley, K., & Ramenzoni, V. C. (2011). Interpersonal synergies. Frontiers in psychology, 2, 38.

Ramirez-Aristizabal, A. G., Médé, B., & Kello, C. T. (2018). Complexity matching in speech: Effects of speaking rate and naturalness. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 111, 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2018.04.021

Repp, B. H. (2005). Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of the tapping literature. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(6), 969–992. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206433

Repp, B. H., & Su, Y.-H. (2013). Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(3), 403–452. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0371-2

Skoe, E., & Kraus, N. (2010). Auditory brainstem reponse to complex sounds : a tutorial. Ear Hear, 31(3), 302–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb272.Auditory

Stephen, D. G., Stepp, N., Dixon, J. A., & Turvey, M. T. (2008). Strong anticipation: Sensitivity to long-range correlations in synchronization behavior. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 387(21), 5271–5278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2008.05.015

Stepp, N., & Turvey, M. T. (2010). On Strong Anticipation. Cognitive Systems Research, 11(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2009.03.003

T., K. C., Dalla, B. S., Butovens, M., & Ramesh, B. (2017). Hierarchical temporal structure in music, speech and animal vocalizations: jazz is like a conversation, humpbacks sing like hermit thrushes. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 14(135), 20170231. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0231

Tielman, M. L., Neerincx, M. A., Bidarra, R., Kybartas, B., & Brinkman, W.-P. (2017). A Therapy System for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Using a Virtual Agent and Virtual Storytelling to Reconstruct Traumatic Memories. Journal of Medical Systems, 41(8), 125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0771-y

Tononi, G., Sporns, O., & Edelman, G. M. (1996). A complexity measure for selective matching of signals by the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(8), 3422 LP – 3427. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.8.3422

West, B. J., Geneston, E. L., & Grigolini, P. (2008). Maximizing information exchange between complex networks. Physics Reports, 468(1–3), 1–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2008.06.003

Yang, Y., Fairbairn, C., & Cohn, J. F. (2013). Detecting Depression Severity from Vocal Prosody. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 4(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1109/T-AFFC.2012.38

Zapata-Fonseca, L., Dotov, D., Fossion, R., & Froese, T. (2016). Time-Series Analysis of Embodied Interaction: Movement Variability and Complexity Matching As Dyadic Properties . Frontiers in Psychology . Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01940 Zbilut, J. P., & Webber Jr, C. L. (1992). Embeddings and delays as derived from quantification of recurrence plots. Physics letters A, 171(3-4), 199-203.